Lauren Velvick discusses her research for The Expanded City. As well as conducting her own research for the project, Lauren will be following the progress of the other artists and providing a critical context for their work and the project as a whole.

Ever since the Expanded City Symposium, I’ve been thinking about demographics with regards to housing. It seemed to me that the way people were grouped assumed that all adults are coupled, or would be eventually, and that housing was being constructed with couples and small families in mind. This vision of society doesn’t bear out in my experience, nor does it acknowledge or anticipate things like the ageing population in Britain. It’s no secret that our society rewards marriage and the construction of a nuclear family, however, the continuing scarcity of jobs in many industries necessitates moving to follow the work, meaning that living as a single adult is requisite.

Furthermore, as rents rise above inflation but wages stagnate, shared housing amongst adults becomes increasingly necessary. Yet, there seems to be little thought given to these kinds of households, beyond the assumption that they are temporary. In order to develop a greater understanding of how they function in terms of interpersonal and financial relations, I have been conducting a series of interviews with people living in different kinds of shared housing. The first of these is transcribed below, and recounts a conversation with Jon Davies, a music producer and postgraduate researcher based in Liverpool whose work you can follow here.

Lauren Velvick: I’m thinking about forms of household that have become increasingly appropriate to the way we live now, and how this works socially and economically. There are things like co-ops that are quite structured, and then the position I find myself in is that I simply can’t afford to live on my own, but neither do I have the time to get involved with a co-op, so I end up having to try and form these temporary households here and there, and being responsible for other adults which can get quite confusing.

In ‘The Consulate’, where you live, is it run like a co-op? What’s the deal?

Jon Davies: The deal is that we have a landlord, and he rents out his house on a general per month rent where he pays the council tax because it’s multiple tenancy – and he’s agreed to pay for the water as well.

LV: So it’s an ad-hoc agreement then?

JD: There’s a certain amount of trust involved.

LV: Since the rental market is so unregulated at the moment, even if you have a letting agent, sign all the contracts and pay all the fees, very little is guaranteed… It’s a case of working out which is the lesser of two evils.

And what about sharing the rent?

JD: We divide it in a tiered system between 16 of us. We’ve got three different tiers.

LV: Were you all living together before you moved in to this place – did you all know each other?

JD: Yeah pretty much, the whole house managed to move together, and before that a few of us had been living in the same place for around six or seven years. This meant that we were all pretty used to living together.

LV: Ah so it’s a long-term arrangement? Not something you’re considering as a stopgap on the way towards married bliss, for example?

JD: It definitely grew from somewhere to live while some of us were still at university, seven years ago when I wasn’t living there. It’s grown from being a bit of a party house to a more workable living space. We have individuals, we have couples and the balance of artists to not artists has really changed. At one point, nearly everyone was in a band, but it’s still really important to understand that there will be noise in the house, as we still have a band practising in the basement

LV: So do you guys have a lease or is it all on trust?

JD: No, there’s no deposit or anything like that, but we do have a contract that’s pretty much rolling as well, but with this one it’s a special case because the landlord used to live here. We all know how to live with each other and we’re not going to trash the place. We’ve also really negotiated it down.

LV: Was that easier because there are a lot of you, or did one person take the lead?

JD: When you’re in such a big group you tend to have people who are better at ‘the art of the deal’, basically. Personally, I don’t get involved with any of that stuff and just trust that the others are looking after my best interests.

LV: That’s interesting, because I did want to ask about…

JD: Hierarchies?

LV: Yeah, since it isn’t strictly a co-op, do the people who do the negotiating make more of the decisions that affect everybody?

JD: Sort of yeah, I guess so, but it’s not as formal as that.

LV: So it’s more of an informal, almost familial relationship? I’m interested in how these relationships develop in a situation where adults are living together.

JD: What’s really nice about this, in comparison to the nuclear family, is that nobody is given predetermined roles or hierarchies. It tends to be based on who’s lived there longest – if you’re new you’re not expected to go around demanding changes.

LV: It’s just interesting how these things fall into place. I think a lot of people, and certainly in my experience my parents, have little idea of what it’s like to live in a group with adults because they were teenagers who had children. Then, during this project when we’ve discussed demographics, it seems like people are simply considered as a child, and then part of a couple, and there’s rarely anything in between, so we need to consider this other demographic that we are part of.

JD: I think there is still a mutual understanding that you have to pull your weight in the house somehow, but just imagine all 16 of us arguing over how we should go about settling bills.

We do have regular house meetings about every two months, which will usually have to do with a certain issue, whether that’s money, or parties or boring stuff like cleaning up after yourself.

LV: With that in mind, space is also a big issue – that’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot because new builds tend to be really short on space. It’s something I wonder about in relation to the housing in Preston, and whether it’s going to allow people to live with, for example, older relatives, because it seems inevitable that with an ageing population and the costs of care increasing… we need to think about how we can fit more than four people into one dwelling?

JD: I think places like Liverpool are really unique in the fact that we’re living in the exoskeleton of wealth.

LV: Liverpool does seem like a singular example, but I suppose you do get this to an extent in all of the cotton wealth towns and cities. Like in Preston there’s an area called Frenchwood which I think is where a lot of the new builds are going to be, and is presumably where the mill owners for foremen would have lived in bigger houses which are still standing while many of the back-to-back terraces have been demolished. Anyway…

JD: I also really like living in a big group. When you’re an adult and start living in a group I guess traditionally that’d be first with your partner and then with your children where there’d be a totally different social dynamic; you’re already locked into this romantic contract with your partner, and then you’re in unbreakable emotional contracts with your children.

LV: You’re also then inextricably responsible for these people. Which is something I wanted to ask about actually, the dynamics of responsibility and care between people… I wonder if it works better with more of you because in a house of two, three or four things can become quite strained. I think people can expect more from other people than is entirely reasonable, for example expecting somebody to behave as though you’re in a romantic relationship when you aren’t. I wonder if there’s a sweet spot, say nine people, where it suddenly becomes a lot easier.

It brings to mind the pop-psychology of introverts and extraverts, whereby people slot themselves into these categories, and I wonder whether that would actually be quite useful in terms of housing and understanding how to get along and how to recognise patterns instead of taking people’s behaviour completely personally.

Maybe that’s what I need to do with this project – develop a chart of ‘housemate types’ that you can fit yourself into.

JD: A total Myers-Briggs thing! There are always more domineering characters, who impose more in space, but then they can also animate the space in a good way. I don’t want it to be a case where we all drearily exist in our individual bubbles.

LV: Perhaps we need to accept the economic reality that for many of us living alone simply isn’t an option, and so you have to renounce a certain amount of control over your living space.

JD: You’re also reducing the level of private property, so in a bedsit situation everyone has to get their own TV licence, pay for energy separately, right down to each having their own bleach spray. In our house we share spices for example.

LV: It’s interesting to consider spices and food, whereby basic ingredients might be cheap but all the things you need to make them taste nice aren’t.

JD: And who as an individual needs a whole rack of spices?

LV: It’s ridiculous! In my house at the moment I’m the only one who uses them and have so much I won’t get through and will have to waste. These are little home comforts that it makes much more sense to share.

JD: You’ve had the nuclear family, thinking pre- and post-structurally, then you have this atomised individual way of life – this late-capitalist being who is a freewheeling cog in the machine, which is the more likely path that people are going to go down at the moment. In a capitalist sense, individuals spawn individuals and the experience of community isn’t taken into account. Whereas in shared living situations, you could potentially reconstitute the family as something else – a sociality that is post-familial but where social contracts still hold.

LV: Exactly, it’s these new forms of adapted social contracts. Friends who have become single parents, for example, seem to have very wide, loosely defined ‘families’ with social bonds that include lots of different people. This also brings me back to considering food and domestic culture, and how these registers of knowledge might be passed along in a social web rather than down a generational ladder.

To be continued…

Left: I’m Blue, You’re Yellow in 2013

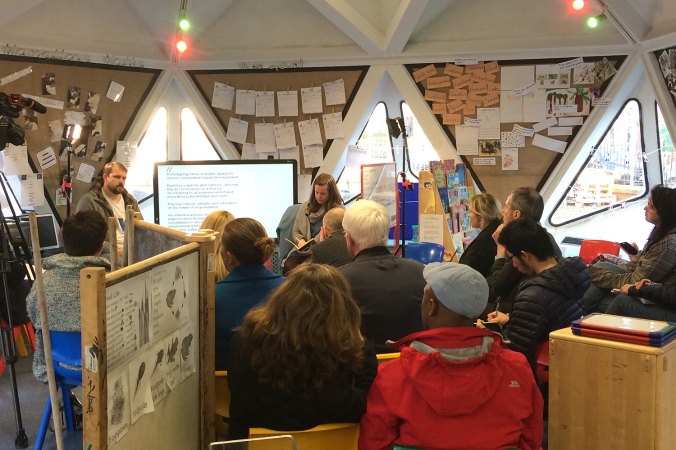

Left: I’m Blue, You’re Yellow in 2013 Top: Rebecca Chesney, David Jacques, Victoria Lucas, William Titley, Joanne Lee

Top: Rebecca Chesney, David Jacques, Victoria Lucas, William Titley, Joanne Lee