Stephanie Cottle introduces Precarious Landscape, an excursion with artists Ian Nesbitt and Ruth Levene to the western bounds of Preston on 8th December 2017. Participant and writer Lauren Velvick reflects on the experience .

Continuing their exploration of Preston’s boundaries, Precarious Landscape saw Ian and Ruth invite an audience on an immersive journey, visiting four sites the artists have encountered whilst conducting their walking practice along the outer reaches of the city.

Embarking the coach in the centre of the city before moving out towards its edges, the event provoked discussions regarding changing landscapes and shifting territories. At each of the four sites Ian and Ruth unearthed historic tales, recanted community memories and indicated views where the landscape itself showed signs of stretching and reforming.

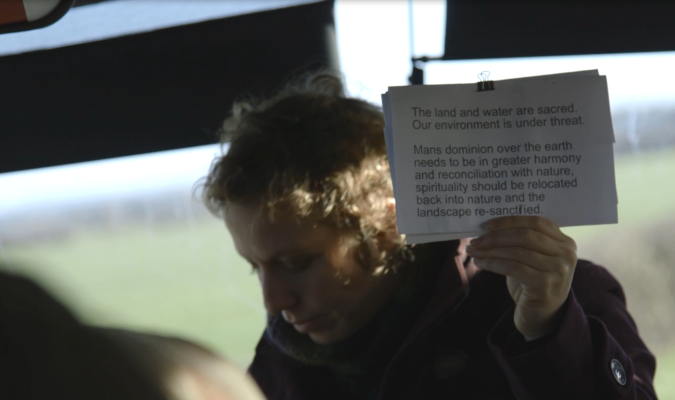

Back on the coach, with the windows framing the view, the artists gave provocations for what might happen to these places in the future. What these made clear is that frequently the driving influence behind the changes in the landscape are external market forces; agriculture, housing development, roadbuilding and the most contested at the moment – hydraulic fracking.

At times the event seemed almost nostalgic, as if mourning for a loss that is on the brink of occurring. We often think back fondly to places we have visited and sculpt the scenes in our minds, we rarely are provided the luxury of stopping to look into the future and envisage what might be lost or gained in the re-imagining of the city, through this experience Ruth and Ian provided the opportunity to both consider and discuss our changing lands.

Stephanie Cottle

Moving out, out, out

The journey from the centre to the edges is still how it has to start, on a bright freezing day. The coach is too big for the narrow lanes that we’ll be travelling down so we’ll have to be ‘decanted’ into a smaller one at some later point. I don’t think I’ve ever been on a trip where the correct coach arrived, perhaps there’s an unsolvable bureaucratic issue at the very heart of private coach hire.

The way that the architecture changes the further you travel out of city centre reflects the changing ideologies and fortunes that fed into its construction; with the cheaper, short-term buildings being thrown up amongst the old sandstone parkside churches, (once black with soot, now blasted back to sandy yellow) then the suburban semis and carefully designed ex-libraries as we reach the outskirts.

Holy wells – the places where deep water surfaces – are an abiding interest for Ruth and Ian, and seem to constitute a nexus where the ideas that the artists’ are aiming to explore with this ‘Precarious Landscape’ event converge. The spiritual and ritual are obviously present here, but so too the bureaucratic and metric, in the ways that holy wells are cared for and managed in order for them to remain within the Catholic tradition, and to remain a part of active and current knowledge within the local and wider community.

The simultaneous ways that sites like this beckon and amass tradition, whether it be spiritual, bureaucratic or both, is exemplified in a story my mother tells. I’ve mentioned before in these posts that Preston is my home town, so that family and old friends occasionally coincide with the project, and this is something I’ve decided to emphasise rather than overlook. With that in mind, when everyone else might be considering the spiritual and ritual more generally, I get stories of ancestors, like my great aunt Agnes who taught at the Ladyewell school, and was apparently an ‘independent working woman’. I suppose that since I’m not a practicing Catholic, Agnes can be my lady of the well.

On the way to our next stop we pass the HMS Nightjar, otherwise known as RNAS Inskip, a naval base on the outskirts of Preston, nowhere near the sea. I know of this place already from being ferried past by an old friend who delighted in sharing tidbits of local esoterica, and it’s a little amusing to hear a couple of people on the trip discussing it, each coming up with different theories as to what it is, both wrong.

Once we alight it’s difficult to intellectualise anything in the freezing wind and piercing sunlight, but we are invited to consider how this land was overlooked until it could be harnessed into the service of industry and capitalism. Described as a marshy wasteland where the locals hunted up to their necks in cold water, now farmland that is in turn contested by those that have come to see this configuration as the way the land should be, and those that would develop it further. Maybe it’s better to remain unrecorded and unproductive – safe.

Ruth and Ian’s ongoing interest in, and knowledge of water processing is relevant here as we consider the recent protests against fracking that have taken place in the area. These may not be explicitly or deliberately spiritual, but they do bring to mind the protests around the Dakota Access Pipeline led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and the designation of ‘water protectors’. Whilst it is easy to think of clean water as a right, and even a common, our access to it is already privatised.

Water then cows then concrete

How can and do we understand land as sacred? – is it a conscious designation or is it in the actions of the land users, and does a collective protective act towards the land make it necessarily sacred? In the discussion that follows we are encouraged to consider the history of protest against land development, and the motivations that it has been driven by. The slogan ‘Cows not Concrete’ * strikes me as particularly ill-conceived and shortsighted, but comprehensible in the context of these rural boundaries.

Irregardless of everything else we have considered and discussed, people are still fascinated by the shimmering of the grass in low sunlight, describing cobwebs and condensation as though they’re the first to have noticed it.

* ‘Cows not Concrete’ was a slogan used in protest to urban expansion in Preston in the seventies, introduced to Ian and Ruth in a conversational anecdote.