As a public introduction to The Expanded City project, a symposium held on June 16 2016 reflected the research concerns of In Certain Places and the commissioned artists through the structure of the event, as well as the content. As we have found through conducting site visits to the areas earmarked for the City Deal housing developments on Preston’s outskirts, a practicality that must be taken into account is the difficulty in reaching these areas using only public transport. One of the commissioned artists, Gavin Renshaw‘s work is partly based around the cultural history of cycling, and he has often made reference to the difficulty in safely reaching the recently opened Guild Loop cycling and walking path, which circles Preston for twenty one miles. Travelling from the centre to the periphery becomes an important issue as we consider how these new developments will relate to the existing citizens and infrastructure of Preston.

As such, the logistical difficulties inherent in the choice of venues and sites for the symposium was a framework around which the day was structured, and was a decidedly positive element, allowing attendees and speakers alike to experience the sites in question first hand, in turn facilitating a deeper appreciation of the topics discussed by the speakers. The day was divided into two halves, with an initial pick-up at Preston train station in a double decker bus, which then went on to transport attendees to the first venue; Woodplumpton and District Club, which sits approximately five miles outside of the city centre. As part of the new housing schemes in question, it has been deemed necessary to provide resources for leisure and culture within the new communities that will be formed. As such, the choice of the Woodplumpton and District Club as the venue for the first, more formal stage of the day is appropriate and poignant. The Woodplumpton and District Club is an old fashioned community club, with facilities for Bowls and Tennis alongside regular activities such as art classes, whist & dominoes and the Women’s Institute. Discussing demographics and regeneration within this context begs the question; what can serve the purpose of spaces like this within new developments?

The two invited speakers that presented during the morning session gave differing but complimentary views on what constitutes a community, of why and how change occurs, and to what extent this can be controlled or directed. First came a presentation from Carolina Caicedo of The Decorators, a multidisciplinary design practice who work with local authorities and public institutions to design and deliver interventions in regeneration areas. These interventions are sensitively tailored to the surrounding community, and often offer a critique of the regeneration in question. Caicedo gave the example of Ridley’s Temporary Restaurant, a project that sought to enliven a struggling market and to facilitate communication between vendors and users. Embedded within the project were certain safeguards, designed to ensure that the restaurant would constitute more than a fashionable eatery that had been parachuted in to a struggling neighbourhood. These included instituting a ‘no bookings’ rule which meant that the limited number of seats would always be open to whoever turned up on the night. Caicedo also emphasized the problems of ill-thought out design in new public spaces, citing a project based around a new public square that had been built in the centre of a development of high-rise apartment buildings, but was underused and desolate.

The pertinent question here seems to be; how can we, in advance, design communal spaces and structures that will actually be used and useful – that will represent something attractive to the local residents. This is where the data and analysis presented by the second speaker, economist Paul Swinney, becomes particularly pertinent. Swinney showed and explained a series of data visualisations that demonstrated, demographically, how differently sized cities are structured, and offered some possible explanations as to why. In considering the areas on the outskirts of cities that are the focus of the Expanded City project, Swinney explained that there is a trade-off between the excitement, resources and employment opportunities of inner city living, compared to the space, peace and safety of the outskirts. He went on to illustrate this point with the example of a young couple who may transfer from choosing a city centre apartment to a suburban house when they decide to start a family. Considering my earlier research into the newly designated employment area to the North East of Preston, where on a sunny weekend I was surprised to find a number of adolescents having chosen this area of relative isolation for their Saturday activities, it is relevant to consider the potential second generation of inhabitants of these new estates, and how they might make use of the outdoor spaces and leisure facilities in unexpected ways.

During this first part of the day Ian Nesbitt and Ruth Levene also presented an extract from their active research project, which has been informed by an earlier practice of collaborative walking and parallel documentation. Nesbitt and Levene deal directly with the question of whether land is public or private, and the points where this differentiation becomes uncertain. Their presentation consisted of a series of photographs taken during their walks, and the reading of extracts from their parallel diaries, written strictly without input from each other. One anecdote neatly illustrated the slightly ludicrous nature of public footpaths, some of which are purposefully blocked, or may not have been used for decades; in trekking along one of these little-used paths Nesbitt and Levene passed a house whose occupant rushed out to greet them, excited that somebody was finally making use of the track.

After the morning session sustenance was provided in the form of a personable pub lunch, and the second half of the day consisted of presentations from each of the remaining artists. The attending Counsellors, local residents and cultural producers once more boarded the double decker bus and were transported to the site of Olivia Keith‘s presentation. Keith’s site specific demonstration outlined her research methods, which involve an openness to chance and serendipity. Keith has been producing large scale, outdoor drawings at sites where older designations meet newer developments, and these are then overlaid with existing and obsolete maps. Keith pointed out the ways in which her observed drawings would match up with the maps underneath in interesting and unexpected ways. This practice also constitutes a way to facilitate conversations with passers-by who live in or make use of these areas, describing how at the meeting of a motorway bridge, country lane and suburb where Keith had chosen for her presentation, she had met a number of multi-generational walkers making a pilgrimage to Bluebell Wood.

Bussed onwards from the North West to North East of Preston we alighted next at my chosen ‘nowhere monument’ that even the Counsellors didn’t seem to have an explanation for. The way in which this de-contextualised wall was reminiscent of a folly or stage set inspired me to instruct the attendees to gather on the oval of grass and wild flowers in between the wall and road to hear a reading linking this area to Robert Smithson’s Passaic, New Jersey. This site is oddly atmospheric, with a scale that lurches between human and industrial amongst the jumble of warehouses and chain cafes.

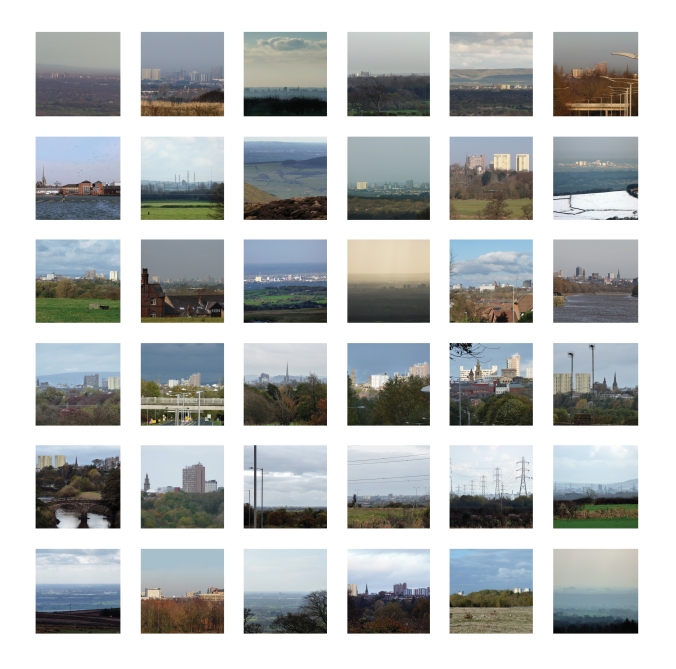

Finally, we headed further East still for a roadside presentation from Gavin Renshaw. This site was decidedly rural, with encroaching hedgerows and a lack of pavements. Following our fluorescent jacketed leader we were led single file to a point where the whole of Preston City Centre is observable in the far distance. This capacity to visually encompass a large and complex site from a distance is an important concern for Renshaw, and is interlinked with his interest in the activity and cultural history of cycling. He spoke of how, from this distance it is possible to take a technically true impression of the City, but one that is also illusory, bringing wooded areas together in distant perspective when in reality they are isolated.

This focus on the nature of representation is a relevant strand that ran through each of the presentations given throughout the day. Nesbitt, Levene and Keith have demonstrated an interest in the disunity between bureaucratic visualisation of a place, and a more intuitive form of mapping based around memory and cultural history. Similarly, the earlier presentations from Carolina Caicedo and Paul Swinney point to the ways in which data and forward planning are useful, but can come unstuck in presenting an overly simplistic and static view of a place and its inhabitants.

Lauren Velvick