At first glance, Gavin Renshaw‘s contribution to The Expanded City is the one that seems to most directly, and pragmatically relate to the potential for new infrastructure. Renshaw has a longstanding interest in cross-country cycling, using this as a tool within his art practice, and as such is personally invested in cycling infrastructure and advocacy. However, in discussing the project with Renshaw, and following the trajectory from its instinctive, habitual beginnings to the way that it has been instrumentalised towards cycling advocacy, complicates such a simple reading.

Renshaw’s initial project, of documenting distant views of Preston from various points around the periphery stems from a number of long-held concerns. An interest in architecture informs the desire to record how monumental buildings such as museums, churches and football stadiums can be brought to prominence or concealed depending on perspective. The process by which Renshaw produces his photographic images is also related to the method of triangulation, whereby accurate mapping is made possible by measuring the angles from a known point to a fixed baseline. This relates in another way to his interest in local architecture, whereby the viewpoints from which Renshaw’s images are photographed can only be noticed from a cyclist’s perspective, constituting a kind of vernacular triangulation.

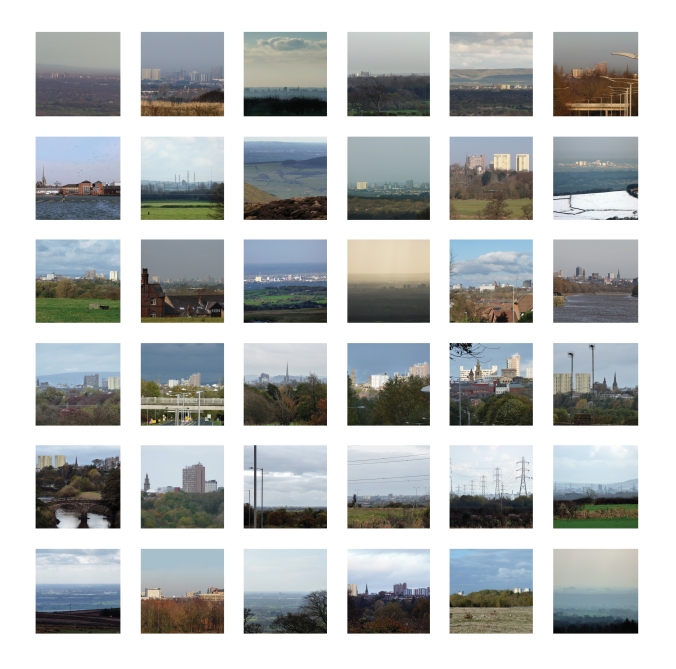

This pragmatic use of architectural and natural landmarks stems from Renshaw’s desire to experiment with the different ways that architecture can be utilised and viewed. By depicting the City from a distance, and using its landmarks as triangulation points, the photographic images that Renshaw produces could be seen simply as a by-product of his research. And yet, these images have an aesthetic value beyond the distances and measurable perspectives that they portray. Taken as individual pictures, the stormy skied, or sunlit views of the landscape and city seem to point to different movements and methods in the depiction of landscape. For example, the more dramatic images taken from a high vantage point nod towards the concept of ‘the sublime’ in Romantic painting.

Although, as Renshaw asserted, these images are not meant to be viewed one by one, and it is the whole collection that constitutes the work. When viewed together it becomes clear that whilst each image is technically ‘true’, the perspective in each can completely alter the apparent make-up of the City. Different buildings and parks gain prominence depending on the angle from which they are viewed, and the temptation to settle on a single iconic depiction of the City’s skyline is thwarted. That these images come as a vast set, each framed in a similar way with the skyline centred, is reminiscent of Mischka Henner’s aerial photographs of vast oilfields and feedlots, whereby socio-politically loaded structures are reduced to distant grids.

The notion of the grid is also a useful one in thinking about Renshaw’s project, considering the way in which his photographic images are visually appealing when viewed singularly, but in agglomeration lose their narrative properties. They are also defined by the act of measurement, and depend upon the position of the observer, rather than the artists eye for their composition. As Rosalind Krauss stated in her discussion of the grid in art in 1979; “grids are not only spatial to start with, they are visual structures that explicitly reject a narrative or sequential reading of any kind.” By this definition Renshaw’s collected images when shown or considered together can be seen as a grid, that rejects narrative by proposing an overwhelming multitude of viewpoints that each depict a simultaneously true and illusory portrayal.

The way that this project has developed as part of the Expanded City is described by Renshaw as an ‘offshoot’. Whilst cycling had been an incidental, yet essential part of his initial research, it is the apparent issues associated with traversing the distance from town centre to periphery that has come to the fore as the project has progressed. In it’s next stage Renshaw’s work may take the form of a roadmap for cyclists, including things like road gradients, places to lock up and bike friendly cafes. This is a pragmatic departure from Renshaw’s original project, but is linked in pointing to the practical concerns of research by bike, whilst foregrounding the importance of individual exploration and relating back to the idea of infinite perspectives. The map will constitute a separate but linked work to the photographic series, and how the latter should be presented is yet to be decided.